The 21st Century has brought with it a massive surge in globalisation, and the power sector has been as affected as any other. Energy security has been a transnational endeavour for many years now, especially for those countries that rely heavily on imports to meet domestic demand. Prominent examples include Japan, with its reliance on Middle Eastern oil imports, or the dominance of Russian gas in many European markets. Around the world, there is a complex web of cross-border energy connections and development partnerships, and energy is playing an increasingly prominent role in international diplomacy.

The globalised energy supply chain, and the need for extensive international cooperation to develop it, was explicitly recognised by world leaders in 2006 at a summit of the former G8 countries – the US, France, Russia, Canada, Germany, Japan, Italy and the UK – at St Petersburg under Russia’s presidency (this was long before Russia’s 2014 suspension from the G8 due to its annexation of Crimea, and the country’s subsequent withdrawal from the group).

“We consider it important to facilitate…exchange of power, including trans-border and transit arrangements,” the countries said in a joint statement. “It is especially important that companies from energy producing and consuming countries can invest in and acquire upstream and downstream assets internationally in a mutually beneficial way and respecting competition rules to improve the global efficiency of energy production and consumption.”

In the globalised energy landscape, natural gas pipelines and electricity interconnectors across borders provide the prospect of international cooperation – and tension. International technology and energy infrastructure partnerships are also an important means for countries on both sides of the deal to boost energy security, develop industry and foster warmer bilateral relations. On the more confrontational side of the coin, strategic energy resources can be weaponised as diplomatic leverage, or to cow opposition on the world stage.

Russian gas and European leverage

Energy has long played a vital part in the geopolitical tensions between Russia and the West. Russian state-owned gas giant Gazprom supplies nearly 40% of Europe’s gas via a dozen pipelines running through Eastern Europe and the Baltic Sea (Nord Stream). This has prompted continental concerns of over-reliance on gas supply from a country of which its relations with the West can be as frosty as its winter climate. These concerns are hardly unjustified, as Russia has shown a willingness to threaten – and carry out, as it did in 2006 and again 2009 – supply cuts to Europe in response to disputes, often with Ukraine, which carries around 80% of the Russian gas sold in Europe.

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalDataWith Europe-Russia relations looking shaky after territorial tension in Ukraine and, more recently, the poisoning of former Russian intelligence officer Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia in early March, the spectre of more gas cuts hangs over Europe amid the seemingly never-ending series of tit-for-tat retaliations.

“The state-backed gas giant Gazprom has steadily increased Western Europe’s reliance on Russian gas in the past few years, with major customers being Germany and the Netherlands,” says Phil Foster, managing director of UK-based Love Energy Savings. “Russia currently supplies 35% of Europe’s gas; in turn, 44% of the UK’s gas is from European pipelines. With Russia as a bottleneck for the UK’s gas supply, diplomatic tensions with the Russian Government could have drastic effects on UK energy prices.”

Putin pivots towards Middle East and Asia

As Europe works to circumvent the gas stalemate by diversifying its gas supply through countries such as the US and Qatar, forcing price reductions from Gazprom, Russia has responded by pivoting diplomatically towards the Middle East and Asia. The new Power of Siberia pipeline is scheduled to start delivering Russian gas to China in 2019, and Russian President Vladimir Putin has launched a concerted diplomatic effort in the Middle East.

During a visit by Putin to Iran in late 2017, Russian energy firm Rosneft announced a $30bn energy partnership with the National Iranian Oil Company, cementing its credentials as a strong alternative partner to Europe and the US. This effort has been aided by US President Donald Trump’s aggressive rhetoric on Iran, which marked a shift away from the Obama administration’s more welcoming approach.

“This masterstroke of energy diplomacy wouldn’t have been possible had it not been for Trump scaring Western investors away from Iran and pushing the country closer towards Russia as a result, which totally reversed the intended dynamic of the Obama administration that sought to reorient Iran in the opposite direction through the multiple concessions that it offered up through the summer 2015 nuclear deal,” wrote economics blog ZeroHedge in a November editorial for OilPrice.com.

US energy deals: sidelining Russia

While Trump’s diplomatic blunders alienate key energy players the Middle East, his administration is working to undermine Russian energy dominance in Eastern Europe, warming relations with important allies in the process. A deal announced last year for the US to supply 700,000t of Pennsylvania thermal coal to Ukrainian state-owned electric utility Centrenergo represents a win-win for both sides on economic and diplomatic fronts.

For Ukraine, the US coal shores up supply at a time when the bulk of its coal mines are controlled by Russia-backed separatists in the east of the country, while strengthening ties to a strong partner in the face of Russian aggression. For the US, the deal helps open up new international markets for American coal as domestic demand flags, and undercuts Russia’s energy influence in the region.

“Today’s announcement will allow Ukraine to diversify its energy sources ahead of the coming winter, helping bolster a key strategic partner against regional pressures that seek to undermine US interests,” said US Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross last July.

Later in 2017, the US signed another deal with Poland, this time to supply American liquefied natural gas (LNG) via British utility Centrica to Polish national energy company PGNiG. The deal could open the door to further LNG contracts in the country, and further supports the US goal of setting itself up as a friendly alternative to Russian supply.

“Russia’s era of go-freeze-yourself foreign policy may be drawing to a close,” the Wall Street Journal noted in an editorial last year. “By offering an alternative to Russian energy, the US empowers its European allies and weakens the Kremlin’s coercive regional influence.”

The era of renewable energy diplomacy

Finite fossil fuels have played a key role in stoking regional tensions and hydrocarbons are also central in the international power plant construction and supply deals that often spur economic development in developing countries while helping import-intensive partner nations meet their energy security goals.

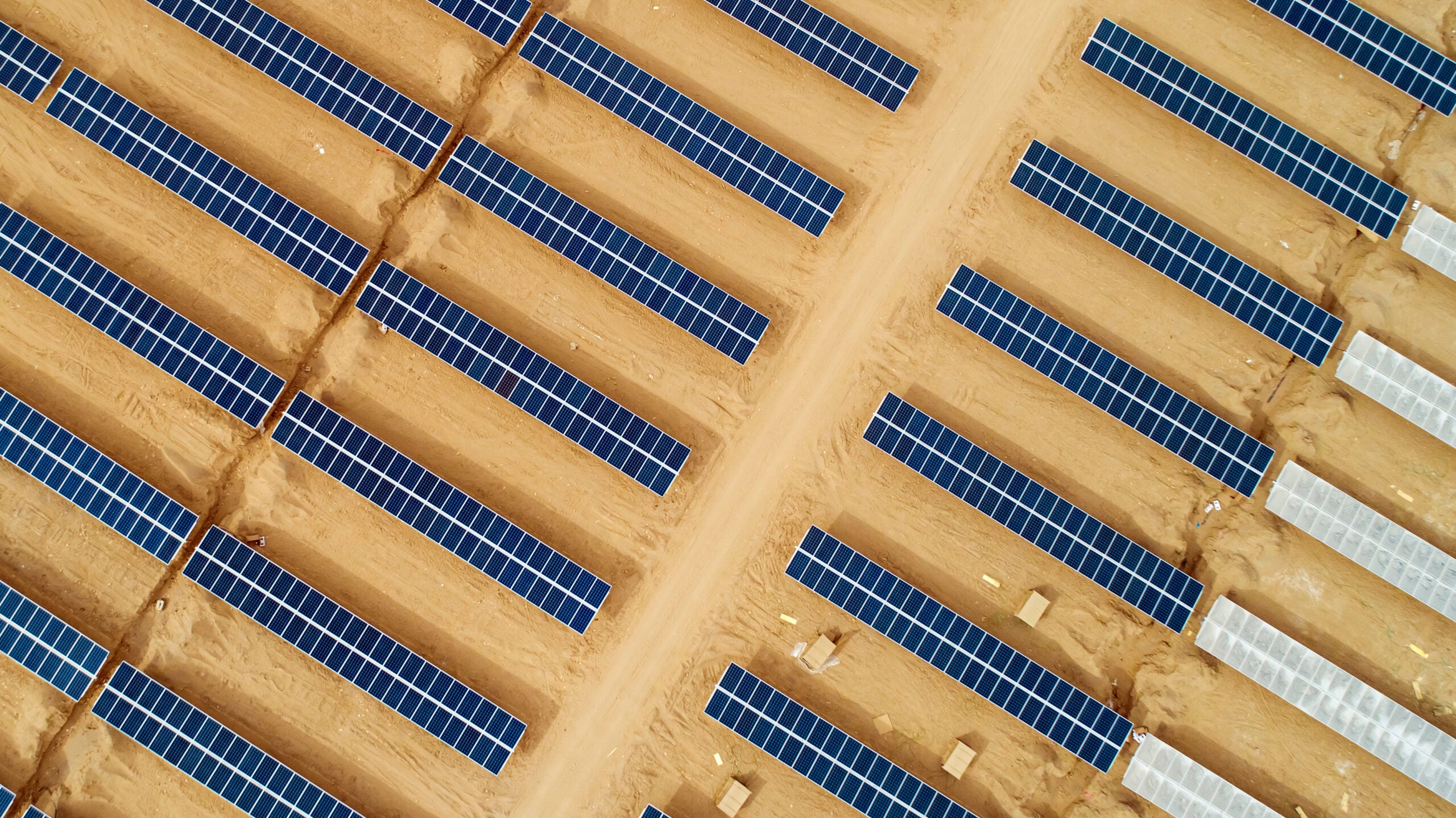

But with the passing of the Paris climate agreement – a tentative, non-binding global deal on emissions reduction but the pinnacle of climate diplomacy nevertheless – the predominance of fossil fuels is fading fast. International partnerships on renewable energy development, through direct international deals or via multilateral and national development banks, are rapidly proliferating, and developed countries no longer have a free hand to shift their emissions through deals with global partners. Environmental campaigns such as E3G and Oil Change International are putting pressure on government-backed development banks to avoid financing coal and gas power projects around the world.

“While some progress has been made, development banks must do more to green their investments,” said E3G senior policy advisor Dr Helena Wright in October. “As a first step, the banks should commit to ending finance for fossil fuel exploration and provide transparency about project emissions.”

Large-scale international partnerships such as the International Solar Alliance (ISA) are creating new leaders in energy diplomacy, as with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi in the case of the ISA. National governments, too, are beginning to recognise that business-as-usual cannot continue in their energy diplomacy efforts. The advisory panel to Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs recently recommended that the government shift its diplomatic efforts away from fossil fuel investments.

“Japan’s energy diplomacy thus far has focused on efforts securing fossil fuel resources; it should now situate renewables as a core of the pillars of the diplomacy in order to realise a sustainable future in collaboration with other countries,” the panel argued, as reported in The Diplomat.

Energy can be used as a carrot or a stick in international diplomacy. With tensions running high in many quarters and a great deal of international cooperation required to meet countries’ climate and energy security goals, here’s hoping the carrot, and not the stick, will gain the ascendancy on the world stage. Focusing on renewable energy collaboration will help countries move past the geopolitical conflict that comes with a global energy system dependent on limited natural resources.

“The potential of renewables to improve energy access, spur sustainable economic growth and create jobs where they are most needed means that a sustainable energy future is not only a necessity, but a common path towards peace and prosperity,” wrote International Renewable Energy Agency director-general Adnan Amin last year. “This will be the job of current and future generations of diplomats.”