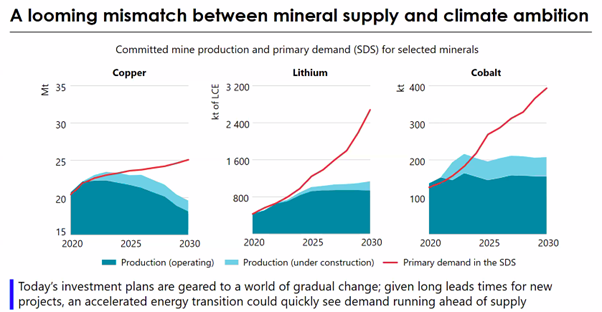

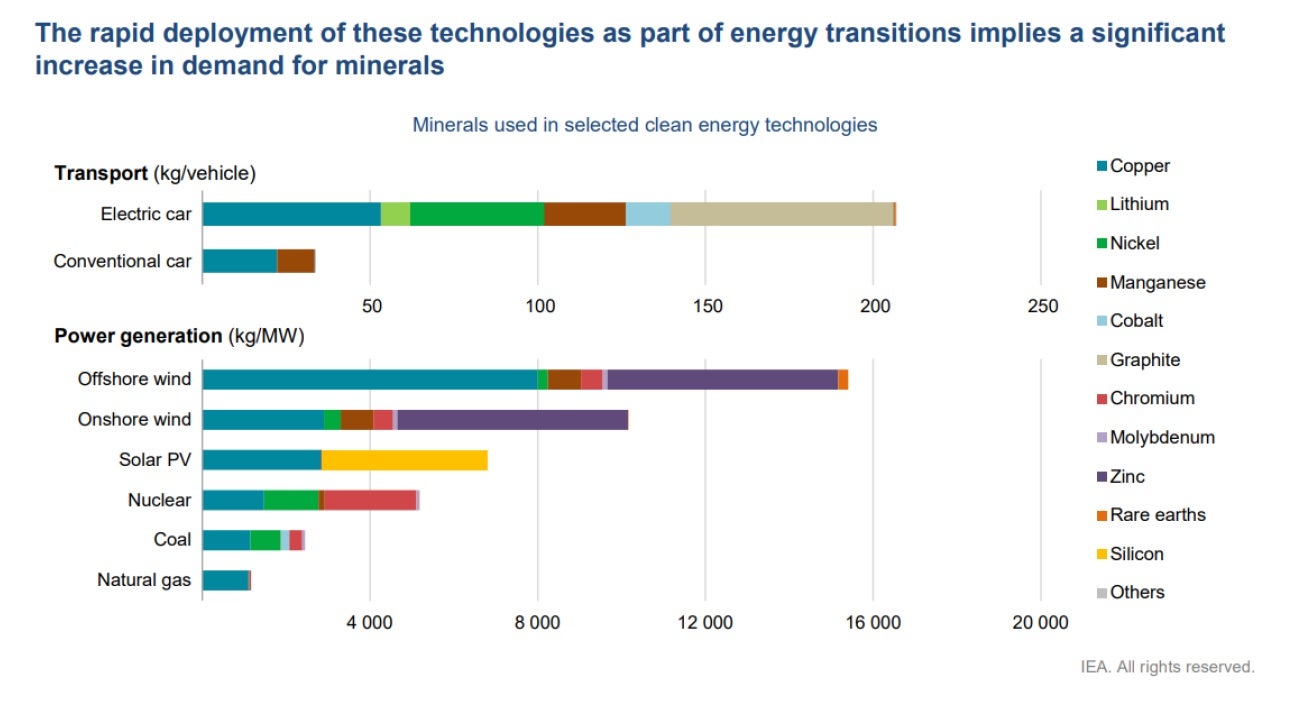

For many key minerals, there is currently a lack of supply chain diversity. Investment plans for mine production of resources such as copper, lithium, and cobalt are typically geared for gradual change, but with energy transition quickly accelerating, we could soon see demand run ahead of supply.

Mining in Kazakhstan

“The World Economic Forum recently said we’re moving towards a mineral-intensive energy system. With the forecasted shortage of minerals, we’re trying to extrapolate some of that into Central Asia, such as Kazakhstan,” explains Christo Visser, senior director of growth in the Middle East, Africa & Central Asia for Worley.

Looking at where Kazakhstan sits globally in terms of the size of mineral deposits available compared to what is being spent on exploration, there is somewhat of an imbalance. This lack of investment in mining is a major issue across the industry, and the untapped potential in Kazakhstan highlights how different the landscape could be if the right projects found funding. For example, graphite is key in the electric vehicle market and the future minerals market, and Kazakhstan has the third largest deposits in the world, but we don’t yet associate the region with graphite.

When it comes to minerals for which Kazakhstan has an established history, we expect to see an increase in exports in the coming years. According to GlobalData, Kazakhstan is the world’s tenth-largest producer of copper, with an output of 755kt last year, up by 11% from 2021. The country accounts for 4% of global production, with the other largest producers being Chile (25%), Peru (11%), China (9%) and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (9%). Exports of copper from Kazakhstan increased by 9% to 1,307kt in 2022 over 2021.

KAZ Minerals is accelerating the growth of copper exports in Kazakhstan with the expansion of its Aktogay mine and the Koksay copper mine, a new project in partnership with China Nonferrous Metal Mining Group. These projects are expected to have production capacities of 80,000t/yr when fully operational. Furthering activity in Central Asia, increased production of copper from Kazakhstan’s mines will sustain growth in Uzbekistan’s copper refining sector. Uzbekistan’s exports increased significantly between 2015 and 2021, with Kazakhstan providing most of the copper ore feedstock.

With copper mining in Kazakhstan ramping up, does this mean that the production of other new minerals could shortly follow? The increased extraction and export of these resources will enhance revenue streams, attract foreign direct investment, and stimulate economic growth. Moreover, the establishment of downstream processing facilities can create a skilled workforce, foster technology transfer, and promote industrial diversification. Kazakhstan’s strategic location, well-developed transportation infrastructure, and favourable investment climate make it an attractive destination for international mining companies.

Accelerating strategic development plans for new mineral production

Currently, announced projects for outputs such as aluminium, copper, gold, and lithium fall short of anticipated demand. “One of the things that we’ve seen in Central Asia is that getting tangled up in bureaucracy can slow down projects getting ‘shovel-ready’. Miners need to find the right partner to help them build a strategic development plan that optimises capital deployment and maximises free cash flow,” says Visser.

One significant way to speed up production is by developing a partnership model between the engineering, procurement, and construction management (EPCM) provider and the mine owner/developer where parties align on key outcomes required. “We believe that alignment across the supply chain towards common goals is key to improving outcomes on major projects,” Visser explains.

Reintroducing lean integrated project delivery to mining

“If we’re to have any chance of avoiding a supply gap, we need to look for accelerated ways to bring additional tonnes to market and new mines into production,” says Simon Yacoub, Vice President and Mining, Minerals & Metals sector lead for the Americas at Worley.

Modern-day projects will need to be driven from a speed-to-market perspective. One way of achieving this is through a lean integrated project delivery (IPD) model. Lean IPD challenges the key concepts in the linearity and sequencing of traditional project development approaches. Instead, it parallels project activities, making key decisions happen earlier in the development timeframe, and using risk-balanced approaches that encourage innovative solutions.

“Typically, engineering sits on the critical path to create something to a precise specification. Taking that specification, we run a procurement process, have it fabricated, installed, commissioned, and passed into use,” explains Yacoub. “It’s very linear and sequential.”

Lean IPD turns this around and reduces the impact of engineering on the critical path. “Our industry contains excellent empirical and experiential datasets on key equipment throughout minerals processing flowsheets, so we know within the realms of relativity what key pieces of equipment are needed early in the development cycle.”

The lean IPD model has proven its value-creation potential across several sectors. “One example is our confidential work with a West Australian miner to increase iron ore production by more than 100mtpa, with three years to do it,” said Yacoub. “This meant production needed to increase by over 180%. Ramp up had to be in months, not years, and name plate had to exceed 100%. Analysts were sceptical. However, by setting ambitious stretch targets, bringing forward vendors and contractor engagement and aligning stakeholder relationships, we were able to improve on historical benchmarked cost and schedule metrics by 20-30%.”

If we evaluate what that 30% first metal to market looks like through the lens of rising commodity prices for new energy materials – and the ability to meet the market a lot faster –the benefit to an owner from a net present value perspective is clear.

“It is not without risk,” adds Yacoub. “However, it’s a risk that is relatively straightforward to manage, and the rewards can outweigh some of the cost inefficiency that is created through the traditional process.”

“When stronger partnerships and alignment is achieved, it’s possible to execute activities concurrently, instead of going sequentially through each traditional stage gates,” Visser adds.

Proving their potential

The growing demand for energy transition materials comes at a key time for Kazakhstan, as the country looks to their natural resources to help accelerate national development. “For Kazakhstan to further capitalise on the energy transition, they must demonstrate a pathway towards being shovel-ready in less time. And by doing so, assets will become much more attractive for investment,” concludes Visser.