In France, this year’s presidential and legislative elections have continued the prevailing theme in western politics over the last few years – a rejection of the establishment. Neither of the establishment parties that have dominated French politics since the 1980s, the centre-right Republicans and centre-left Socialist Party, had a candidate that lasted through to the second round of voting on 7 May, with centrist candidate Emmanuel Macron, leading a party that had only been established 13 months previously, seeing off hard-right contender Marine Le Pen in the run-off.

The legislative election in June was also a bruising encounter for France’s political establishment, with Macron’s La République En Marche securing a substantial majority in the National Assembly, at the expense of the Socialist Party and the Republicans.

In the French power generation landscape there is no energy source more establishment than nuclear power, and this important sector is also bracing for impact as under Macron the country looks to continue its gradual transition away from nuclear. So why is nuclear so important for France – why is the country retreating from it and what could be the effects?

Nuclear: France’s establishment power source

From Henri Becquerel’s discovery of natural radioactivity in the late 19th century to the world-renowned research conducted by Pierre and Marie Curie, France has a long and pioneering history with nuclear power.

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalDataThe country’s development of civil nuclear power stations began in earnest after the Second World War and accelerated in the wake of the oil crisis in 1973, when Prime Minister Pierre Messmer unveiled a plan to meet France’s entire electricity demand with nuclear power, thereby improving energy security and tapping into the heavy engineering strengths of French industry. The slogan at the time was: “In France we do not have oil, but we have ideas.”

France didn’t end up building quite as many nuclear plants as envisioned in the ‘Messmer Plan’ – which aspired to have around 80 plants built by 1985 – but it still drove French energy policy for decades afterwards. Today, the country’s 58 nuclear power plants account for more than 70% of its electricity production, the highest national share in the world.

However, over the last few years, there are signs that one of France’s biggest energy ideas is beginning to wear thin, at least in the eyes of many of its politicians and people. The 2011 Fukushima-Daiichi nuclear plant disaster in Japan was a watershed moment for nuclear in Europe, with Italy deferring and subsequently cancelling new nuclear construction projects, and German Chancellor Angela Merkel kick-starting the country’s ‘Energiewende’ (energy transition), of which phasing out of Germany’s civil nuclear fleet is a key component.

France’s energy transition

At the time, then-President Nicolas Sarkozy stood by France’s nuclear sector, refusing to follow his European counterparts down the anti-nuclear path. Sarkozy’s immediate successor, François Hollande, however, was a different story.

Reducing France’s dependence on nuclear power was one of Hollande’s key platforms as a presidential candidate, and in August 2015 the National Assembly voted in favour of France’s own ‘transition energetique’, which, along with increasing the share of renewables and cutting fossil fuel consumption, stipulated a reduction in the share of nuclear power to 50% of electricity production by 2025. The Energy Transition for Green Growth bill was given final approval by the National Assembly in July 2016.

The fate of nuclear power was a key battleground in the recent presidential election, with Macron essentially supporting Hollande’s Germany-style energy transition and nuclear fleet reduction goals, while Le Pen argued for continuing with the ongoing nuclear plant lifetime extension works and full renationalisation of majority state-owned energy company EDF.

“It’s not good to have 75% of our energy come from nuclear,” argued Macron, and added, “I will keep the energy transition programme and hence I will keep the 50% cap [by 2025].”

Why the nuclear retreat?

With Macron and his party victorious, the timeline for achieving this goal may be uncertain, but what seems clear is that the sun is beginning to set on the golden age of nuclear as France’s primary energy source. So why has a country that has historically been Europe’s most enthusiastic nuclear adopter started to turn its back on the technology?

Just as energy security was a fundamental justification for kicking off France’s nuclear roll-out in the post-war period, the same principle is working against it today. Compounding the issue of France’s reliance on the nuclear sector is the fact that all plants in the country were built with the same pressurised water reactor (PWR) design. This standardisation facilitated the quick and efficient construction of a large nuclear fleet, but now it leaves plants – the average age of which is now more than 30 years – open to generic risk, with the technical issues discovered at one site potentially affecting many more, or at least requiring extensive and widespread safety checks.

This is not just a theoretical risk; events over the past year have demonstrated the fragility of France’s reliance on EDF’s nuclear plants. Investigations by French regulator the Nuclear Safety Authority (ASN) were initiated last year after it was discovered that deficiencies in the steel used for reactor vessels could be endemic in EDF-operated PWR plants, prompting the closure of around 20 of the country’s 58 plants and fears of electricity cuts over the winter period due to the ensuing power crunch.

EDF and Areva’s third-generation PWR design, the European Pressurised Reactor (EPR) hasn’t been a much better advertisement for nuclear technology. The first two EPR construction projects in Europe, at Flamanville in France and on Olkiluoto Island in Finland, have both suffered spiralling budgets and delays due to the complexity of the design.

A massive contract to build another EPR plant at Hinkley Point in the UK – finally approved by the British Government in September after significant controversy over its size and cost – provided a boost to EDF and the EPR, but in July, around two years before construction is due to start, EDF warned that project costs are likely to exceed its original estimate by more than £2bn, with possible delays of 15 months and seven months for the first and second reactors, respectively.

Reducing nuclear dependence: a tricky proposition

Several years of quality concerns, badly managed new-build projects and the financial woes of keystone companies such as EDF and Areva make it easy to understand why the French public and policymakers are in favour of reducing the nuclear share, but actually accomplishing the goal of cutting nuclear production to 50% of the country’s total output by 2025 is looking like a tall order.

President Macron has the heart of a pragmatist and even before the election signs were emerging that the timing of the nuclear ramp-down under the new president could change. Although a Macron spokesman told Reuters in early May that “we will respect the trajectory laid out by the energy transition law”, an anonymous source close to the campaign admitted to the news service that the 2025 deadline was “not cast in stone”. Bloomberg reported, again based on an anonymous source, that the 50% target is more likely to be hit between 2030 and 2033.

After the election, new Environment and Energy Minister Nicolas Hulot told reporters at a G7 climate summit that the government was committed to the programme. “We are going to close some nuclear reactors and it won’t just be a symbolic move,” he said. Significantly though, Hulot would not be drawn on the timing of these closures.

Cutting France’s primary source of energy by such a large percentage within just eight years presents a host of complications. Issues include employment concerns, as the sector supports hundreds of thousands of workers, and the health of the nuclear industry and its skills base. Of course, the key question is, what will make up the energy deficit as plants continue to be taken offline?

Can renewables fill the gap?

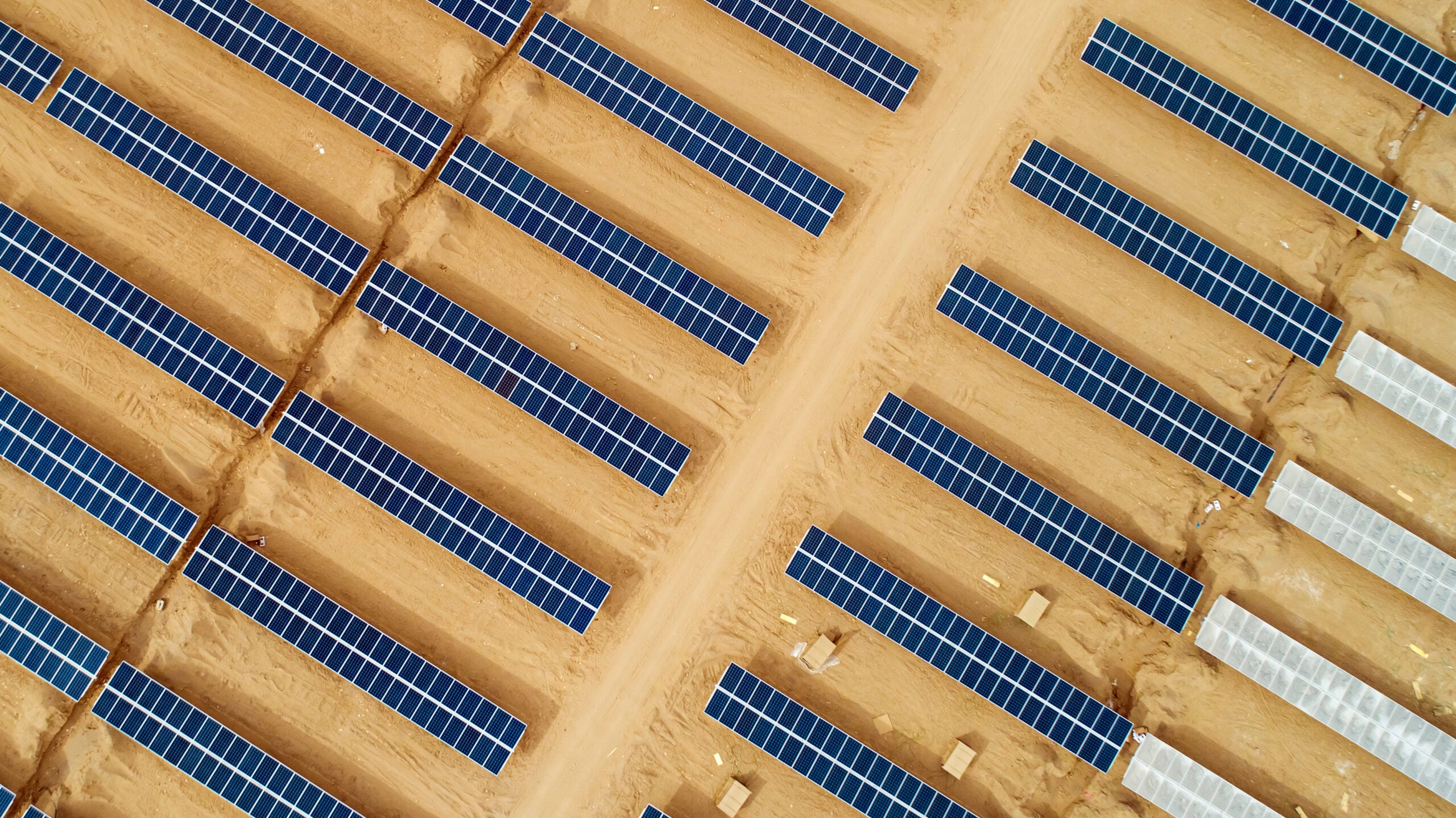

Macron is planning large-scale tenders for wind and solar projects across France, with 26GW worth of renewable projects promised to be up for grabs by 2022. The aim is to double France’s wind and solar capacities – currently at approximately 11.7GW and 6.8GW respectively. However, replacing sources of low-carbon baseload power with intermittent renewables is no easy feat, and could have profound implications for the country’s decarbonisation efforts.

Several groups of scientists and environmental activists, including the French Academy of Sciences and a 45-strong group of climate scientists and writers dubbed Energy for Humanity, have highlighted the role that nuclear needs to play in the fight against climate change, and used Germany’s experience of closing down nuclear plants as a warning.

“Any reduction in France’s nuclear generation will increase fossil fuel generation and pollution, given the low capacity factors and intermittency of solar and wind,” Energy for Humanity wrote in an open letter to President Macron in July. “Germany is a case in point. Its emissions have been largely unchanged since 2009 and actually increased in both 2015 and 2016 due to nuclear plant closures. Despite having installed 4% more solar and 11% more wind capacity, Germany’s generation from the two sources decreased 3% and 2% respectively, since it wasn’t as sunny or windy in 2016 as in 2015. And where France has some of the cheapest and cleanest electricity in Europe, Germany has some of the most expensive and dirtiest.”

Germany’s experience with the Energiewende does strike a strong cautionary note for France as it attempts an approximate emulation of the process. In France’s case, the nuclear retreat is undoubtedly more necessary than it was in Germany, but Macron shows signs of treating this complex issue with the thought that it deserves. Decisions on extending the lives of many of EDF’s nuclear facilities will need to be made once the ANS has made its recommendations, and Macron is reportedly even considering a UK-style Contracts for Difference system to incentivise the construction of new, more modern plants.

Whatever the case, reducing what looks like an unhealthy reliance on nuclear is a sensible long-term goal for France. But accomplishing this by the ambitious and somewhat arbitrary date of 2025 will likely be more trouble than it’s worth.