While 2025 saw clean energy account for the bulk of new capacity additions, grids continued to lag, struggling to integrate this new supply – not rendering the energy transition moot but certainly raising concerns about the pace of change. On top of this, electricity demand is rising faster than ever, and the source of growth is no longer just homes or traditional industry.

Three key themes set the tone for the energy industry this year: data centres wreaking havoc on global power systems; tariffs doing the same to supply chains; and worsening grid bottlenecks alongside persistent efforts to flip this around.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

Data centres: boon or burden for the energy transition?

In the past year, data centres have moved into the heart of global energy dialogue, not only reshaping the industry’s supply chains and investment decisions but also forcing the sector to rethink how power is generated, distributed and consumed.

Data centres are becoming a major driver of global electricity demand, with their consumption set to reach 945 terawatt-hours by 2030 – roughly 3% of global consumption. By that point, in the US, where data centre growth is most expansive, they are expected to use more power than all other energy-intensive industries combined – including aluminium, steel, cement and chemicals.

The power industry has therefore been trying to answer: how will we meet this demand? For one, data centres can be built within three years, but the energy systems they require often take far longer to develop. They are also extremely energy-intensive, operating 24/7 with virtually zero tolerance for outages, necessitating a load profile not all power sources can easily guarantee.

The tech and energy worlds are responding with a mix of strategies including buying from the grid, negotiating long-term power purchase agreements (PPAs) and co-locating data centres with power generation facilities.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataGas-fired power appeals as a solution as it “offers better grid stability than other energy sources, with the flexibility of being able to be quickly started and stopped and the reliability of constant, strong power generation,” says Pavan Vyakaranam, senior power analyst at Power Technology’s parent company, GlobalData.

In the US, he notes that gas also has a political edge: “With Trump’s pro-fossil fuel policies in place, it is both more economical and, from a clearances perspective, easier to roll out gas-based projects than others like renewables.”

These circumstances have presented a new opportunity for gas producers, with 2025 seeing many utilities like Entergy Louisiana, NextEra Energy and GE Vernova revise their plans to invest in gigawatt (GW)-scale projects aimed squarely at meeting data centre demand.

With data centres driving more gas power capacity and their demand piling onto already stretched grids, many naturally worry that their rapid growth could slow or even derail the energy transition.

To this, Vyakaranam responds: “Data centres are indeed making the energy transition more complex – but not unworkable.”

In the short term, he confirms that “their large, fast-growing demand may force grids to rely more on gas and delay the retirement of some fossil capacity, especially where transmission and storage are lagging”. According to GlobalData, gas and coal together will meet more than 40% of data centre electricity demand until at least 2030.

“At the same time,” he says, “hyperscalers are among the biggest buyers of renewables and are increasingly backing energy storage, advanced grid tech and even early-stage clean energy options like fusion and next‑gen nuclear.”

While renewable energy “cannot be a sole solution for data centres without any backup power” due to its intermittent nature, the rapid growth of the energy storage market – driven in large part by hyperscalers themselves – is now making renewables just as competitive. GlobalData forecasts that renewables – currently responsible for around 30% of data centre power supply – will contribute at least half the share by 2030.

Many tech giants have turned to renewables in the form of PPAs. Amazon, Microsoft, Google, Meta and Apple currently stand as the largest corporate buyers of renewable energy globally and have contracted almost 50GW of capacity to date.

Hyperscalers are also exploring co-location, through which developers can cut development timelines, costs and grid congestion. Google has partnered with Intersect Power and TPGRise Climate to develop co-located renewable projects, while Chevron, Engine No. 1 and GE Vernova are looking to supply 4GW of co-located gas capacity.

However, nuclear power is emerging as the most compelling co-location option due to “synergies in load profiles”, says Harminder Singh, GlobalData’s director of power research and analysis. “Data centres generally aim for a downtime of less than five minutes per year. Nuclear power plants have a flat baseload generation profile, hence are able to meet this requirement.”

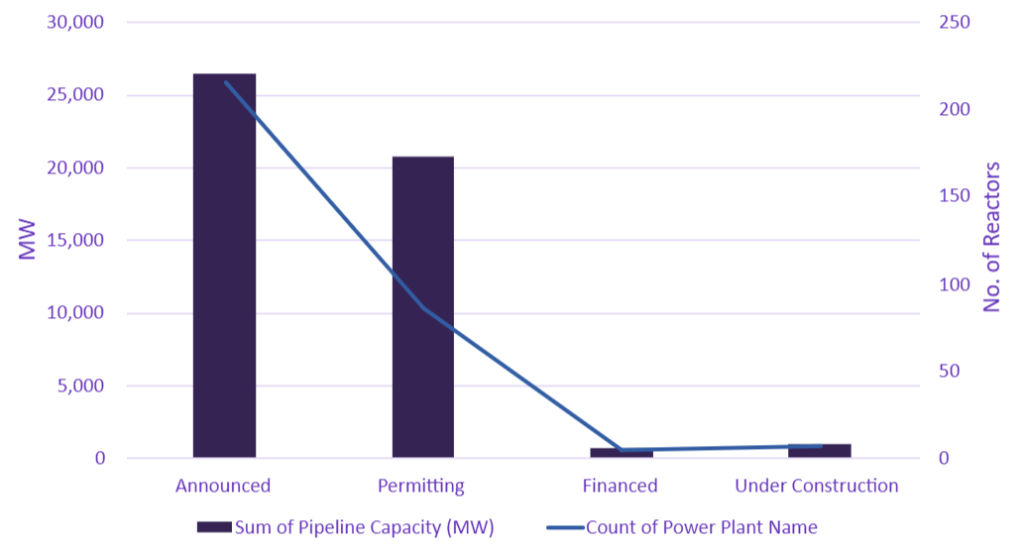

Small modular reactors (SMRs) are at the centre of this shift, as their smaller size allows for easier on-site deployment, minimising risks of transmission loss. To date, around 25GW of data centre-linked SMR capacity has been announced.

In 2025, the SMR-data centre relationship moved from concept toward commercial reality. “We saw multiple deals for SMRs to power data centres, providing a financing model where high‑cost nuclear is matched with very stable, creditworthy demand,” Vyakaranam explains.

Policy support has also become more concrete, with Vyakaranam pointing to the US’ shift in federal funding and programmes “from broad R&D support to supporting commercially realistic SMR projects that can be built this decade”, making the technology more “bankable”. Similar government-backed deployment pathways for SMR-powered data centres were evident in the UK and Canada.

“Nuclear projects require relatively more time for buildout, thus won’t be favoured over gas or renewables in the near-term,” Vyakaranam notes. “However, from 2030 onwards, data centres will be increasingly powered by nuclear, then renewables, then gas.”

GlobalData forecasts that at least 3GW of additional data centre-linked SMR capacity will be commissioned in the next three years, and nuclear deployment for data centres will peak between 2031 and 2035.

Amid these discussions, many have questioned what would happen if the data centre hype turns out to be a bubble, but Vyakaranam assures: “Compute use demand is strong, so a total bust is unlikely. If companies do overbuild, they can fall back on slowing new capital expenditure, leasing excess space and repurposing sites for other energy‑intensive industries, or selling assets to infrastructure investors.

“The associated grid upgrades and clean power contracts would still support the energy transition,” he concludes. “Despite the burden they are putting on power systems now, over time, if policies and grid planning catch up, data centres are more likely to reshape the energy transition – towards more firm, low‑carbon capacity and demand flexibility – than to derail it.”

Supply chain: gas bottlenecks, renewables’ tariff hit and T&D triumphs

The challenge for gas-fired power amid the energy transition has oddly been not demand but supply. While the gas industry cheered the boost from data centres, the equipment market has struggled to keep up with their demand – “on top of the substantial volumes of new gas-fired capacity utilities planned to meet overall electricity demand growth”, Singh adds.

New gas turbine orders have surged over the past two years, something that equipment manufacturers were unprepared for having made limited investments in manufacturing capacity.

As a result, turbine deliveries for new gas plants now face delays of several years. GE Vernova and Mitsubishi, for example, both see order backlogs stretching into 2028 and 2030.

“This has hampered the development of new gas-based power, forcing developers to reassess timelines and driving up project costs,” Singh says.

Meanwhile, 2025 delivered a mixed bag for the renewables supply chain.

The solar supply chain is feeling the tension between supply and policy. Module production has grown exponentially since 2019, with key manufacturers like Jinko, Longi and Trina dramatically scaling output. What resulted was oversupply, which has consequently lowered the costs of solar projects.

This progress, however, was slightly offset this year by trade policies. In the US, GlobalData estimates that Trump’s tariffs could raise the cost of utility-scale solar projects by around 10%, driven by a 30% cost increase for modules and inverters – components the US still relies heavily on imports for.

Despite ongoing efforts to expand domestic manufacturing, in the foreseeable future, “the tariffs and new anti-dumping and countervailing duties on South East Asian cells and modules are likely to create genuine supply bottlenecks and unprecedented challenges for renewable energy deployment”, Singh warns.

The offshore wind supply chain has been hit even harder. The latest tariff hike on steel and aluminium – integral to wind turbines – has significantly driven up offshore wind project costs. For instance, Dominion Energy’s 2.6GW Coastal Virginia offshore wind farm saw its capital cost rise from $10.9bn to $11.2bn following the tariff blow.

These pressures are compounded by the Trump administration’s broader hostility towards offshore wind, which has already triggered project delays and heightened investor uncertainty.

“Forecasts are quite pessimistic in the near-term,” Singh concedes, but notes that these supply chain woes still “didn’t stop the build-out of new renewables”.

Transmission and distribution (T&D) equipment manufacturers enjoyed a far more positive year, seeing active investment flows into capacity expansion. Cable makers like Prysmian, Nexans and NKT Denmark announced investment in the millions and even billions to ramp up production, while transformer suppliers including Hitachi, Hyundai Electric, Siemens Energy and Toshiba are scaling up capacity with projects spanning multiple continents.

The T&D equipment market’s financial pulse is growing stronger, reflecting the industry’s increasing focus on improving and expanding grid infrastructure. “These investments will be critical to integrating new power capacity and ensuring the stability of increasingly complex grids,” says Singh.

Grid constraints ease with reform and storage

Even with robust T&D investments this year, power grids are still ill-equipped; interconnection queues have grown longer in 2025, unable to connect new capacity – most of which are solar and wind. As it stands, grid bottlenecks remain a major hurdle to a smoother clean energy transition.

However, grid reforms are beginning to ease some of these constraints. In 2025, the US updated its regulatory rules to streamline connection processes; the UK’s energy regulator announced similar plans, accelerating almost 8GW of connection; and Brazil permitted 10GW of projects to leave interconnection queues without penalty. Transmission infrastructure expansion is also going strong, with high-voltage direct current (HVDC) projects finding favour due to lower network losses.

China is leading the way, specialising in ultra-HVDC technology and planning more than $200bn (1.41tn yuan) in investment in transmission lines by the end of the year. In Europe, subsea HVDC interconnectors such as the Viking Link and North Sea Link are transmitting electricity across hundreds of kilometres beyond national borders; this year, developers began exploring the feasibility of even longer cables spanning thousands of kilometres, connecting Canada to the UK or Australia to Singapore.

While grids scramble to keep pace, energy storage seeks to hold down the fort.

Among different technologies, batteries stand out most, with GlobalData projecting that 2025 will see annual battery capacity additions that are nearly double those of 2024 – leading to a 63% year-on-year increase in cumulative global capacity.

“Battery storage is no longer a supporting actor but a necessity to modern power systems,” Singh says. “We saw multiple applications for batteries emerge this year, from energy shifting and black start capabilities to providing ancillary services in grids and capacity support for system adequacy.”

As rising electricity demand burdens the grid still further, batteries will also “help ease grid congestion by storing surplus power during high production periods, reducing curtailment and lowering grid integration costs”. Recognising this value, hyperscalers have struck various deals with battery storage developers this year to help manage their own power needs.